If you live in Houston, you’ve seen how fast water can take over a street. That’s why the “San Jacinto Preserve” debate hits a nerve. People don’t just argue about growth. They argue about where stormwater goes when a huge piece of land changes. And right in the middle of that argument sits one tool that turns opinions into numbers: a topo survey.

Lately, the conversation has spread across local posts and neighborhood threads. Some folks worry about flooding downstream. Others talk about housing needs and new roads. Still, the core question stays simple: Will changing this land push water somewhere else? A topo survey helps answer that question in a way a headline never can.

Why this debate feels personal in Houston

Houston doesn’t need a reminder that “water finds a way.” We’ve watched heavy rain stall freeways, flood subdivisions, and fill bayous in a few hours. Because of that, any large development near rivers and creeks sparks strong reactions. People picture water rising, not just new rooftops.

Here’s the problem: most arguments start with “I think.” That sounds normal, but it doesn’t help engineers, planners, or homeowners make a safe call. Flood risk comes down to inches, slopes, and paths. So, when a project sits near areas that already carry floodwater, details matter more than hype.

Floodplain vs floodway

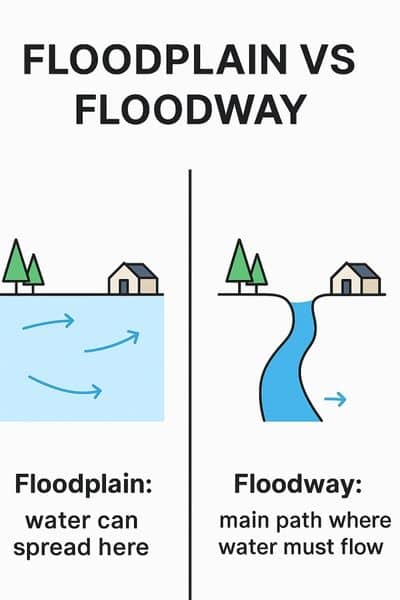

A lot of people use “floodplain” and “floodway” like they mean the same thing. They don’t.

A floodplain is land that can flood. During major storms, water spreads out into that area.

A floodway acts more like a moving lane on a highway. It’s the main corridor where water must flow during a big flood. If you block that corridor, the water doesn’t disappear. Instead, it squeezes, speeds up, or shifts sideways. Then it hits other areas harder.

So, when you hear “floodway,” you should think: this zone carries the flow. That’s why rules get stricter there, and that’s why people react so strongly to big grading or fill plans near it.

Where a topo survey becomes the “truth layer”

People can stand on a site and say, “This looks flat.” But your eyes can’t measure subtle slopes across hundreds of acres. Also, a site can look high in one spot while a low swale hides ten yards away.

A topo survey solves that. It shows the ground shape in a way designers can trust. More importantly, it shows how water likely moves across the site right now. Then engineers can model what happens after the work starts.

In other words, the topo survey doesn’t “predict the future” by itself. However, it gives the clean, hard numbers that every good flood study needs.

The details that matter in floodway areas (not just “contours”)

If your goal includes flood risk decisions, a simple topo map won’t cut it. You need the kind of topo survey that captures how water actually travels.

Breaklines: the hidden feature that changes everything

Contours look nice, but they can miss sharp changes in grade. Breaklines fix that. They trace the edges of key features like:

- the top and bottom of a ditch

- the edge of a creek bank

- the ridge of a berm

- the lip of a swale that steers runoff

Because water follows these edges, breaklines help the map match reality. Without them, a model can “smooth out” the ground and send water in a direction it never takes in real life.

Drainage features: the spots where water decides

Water doesn’t just flow across grass. It drops into inlets, runs along ditches, and funnels through culverts. So, a strong topo survey captures things like:

- ditch flowlines (the low center line)

- culvert inverts (the bottom inside of a pipe)

- channel bottoms and edges

- crossings and low points where water pools first

These points matter because they control where water speeds up, slows down, or backs up. And in Houston, that can mean the difference between “wet yard” and “water in the house.”

Elevations you can trust: the vertical reference

Two maps can show the same shape yet still disagree on height if they use different vertical references. That sounds small, but it can wreck a project. A few inches can change whether water flows toward a pond, into a street, or against a slab.

So, surveyors tie elevations to known control points and use a clear vertical reference. That keeps everyone on the same page—survey, design, and review.

Why “adding fill” can create loud fights

You’ll often hear: “They’ll raise the site to make it safer.” That can help the site itself. But it can also push problems outward.

Think of floodwater like traffic. If you narrow a lane, cars don’t vanish. They jam up and spill into other lanes. Water acts the same way. If fill takes away storage space in a floodplain or blocks the main flow in a floodway, the water spreads elsewhere. Then neighbors feel the impact.

That’s why these topics go viral. People don’t want a technical debate. They want to know one thing: Will this make my street flood more?

A topo survey helps answer that by showing the existing ground, the low paths, and the places where water already “wants” to go. Then a design team can test what changes after grading.

What this means for homeowners and small builders

You might read this and think, “I’m not building a mega-project.” Fair point. Still, the same idea hits everyday projects.

If you plan to buy land near a creek, build near a bayou, or regrade a lot that already floods, you face the same physics. You just face it on a smaller scale.

For example, a homeowner might want to raise a backyard to stop pondering. That seems harmless, yet it can push water into a neighbor’s fence line if the lot drains across property lines. Likewise, a small builder might raise a pad site for safety, but the driveway and yard grading can steer runoff into the street or next door.

So, you don’t need a political debate to use the lesson. You just need to respect the flow paths.

Bringing it back to the San Jacinto story

The “San Jacinto Preserve” debate matters because it forces the real question into public view: How do we measure flood impact before we change the land?

People can argue about growth all day. However, water won’t negotiate. It will follow slope, gravity, and the space available to move. That’s why a topo survey plays such a big role in floodway conversations. It gives the shared ground truth that both sides can examine.

The takeaway

If Houston teaches anything, it’s that flood risk shows up fast and costs a lot. Because of that, the smartest move starts earlier than most people think. It starts before the grading plan, before the stormwater model, and before the permits.

It starts with a topo survey that captures the features of water obeys—banks, ditches, culverts, and true elevations. Then decisions become clearer, designs become safer, and the debate becomes less emotional. Most of all, people get answers they can map, measure, and explain.